Dubai is one of the seven sheikhdoms that form the United Arab Emirates. Until the 1960s, this inhospitable stretch of desert on the Persian Gulf had no electricity or running water. It was the discovery of oil in 1966 that triggered the wave of modernisation that was to drastically change the face of the city. In record time, Dubai transformed itself into a global city where trade, real estate and tourism became its most important economic sectors. The population increased from 183,000 inhabitants in 1975 to nearly three million today. Of these, only 10% are native Emirati, the rest being expats who reside and work in the Emirate temporarily. 75% of the population is male.

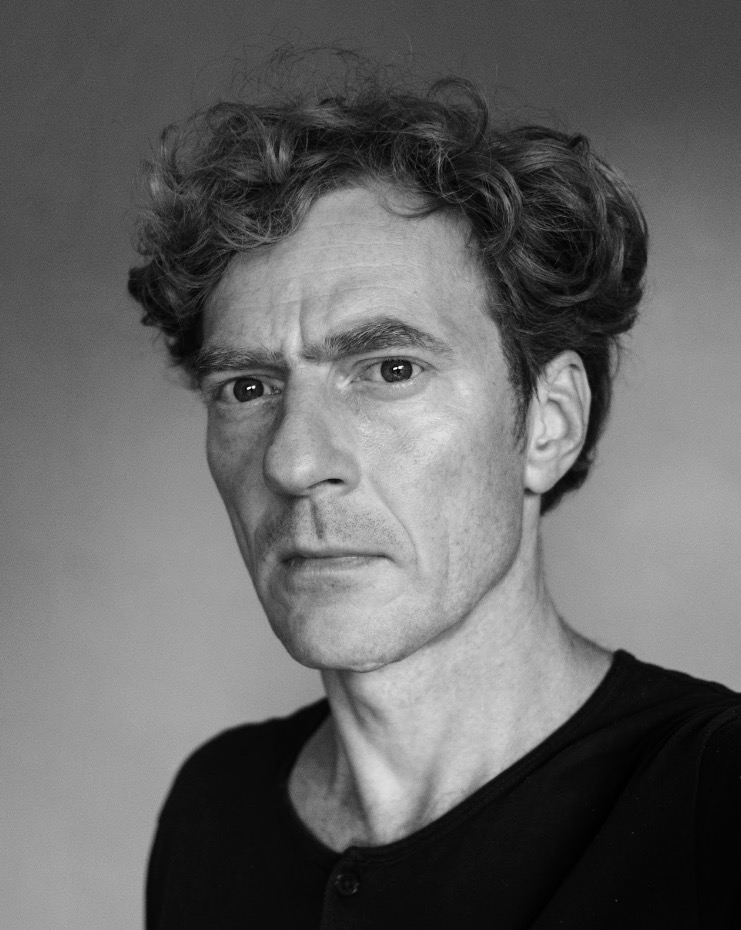

Nick Hannes travelled to Dubai five times between 2016 and 2018, considering the city as a case study in breakneck, market-driven urbanisation; the ultimate playground for globalisation and capitalism without limits or ethics; or, to put it another way, Dubai is an out-of-control entertainment hall, meticulously designed to serve unbridled consumerism.

Hannes’ photographs function as a razor-sharp knife that uses humour and irony to slice through this metropolis of the future. What remains, in the words of the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, is a “Generic City”, without history, personality or identity; a city that is “indifferent to its inhabitants”. To Hannes, it is a place where “human activities are reduced to their economic value”.

The Netherlandish painter, Hieronymous Bosch, painted his iconic triptych Garden of Earthly Delights about 500 years ago. The central panel depicts a fake paradise, right before the Fall. It is a dystopian image to which Hannes – from his outsider position – likes to refer. He reveals Dubai as a Theatrum Mundi, at times with dismay, at others with dumbfoundedness, but always with a desire to understand. Is a model like Dubai economically and socially sustainable – or are we still, 500 years after Bosch, living in the same ill-omened theatre of the world?